Wednesday, March 28, 2012

(Review) Gary Ross' "Hunger Games"

You're probably tired of hearing about "The Hunger Games," and I get that. You probably feel it's just another over-hyped book for teens that's all sugar and no substance, which I'd disagree with completely. Or maybe you're one of those people who feel that since the plot is so similar to the Japanese movie "Battle Royale" that you're turned off by the prospect of this story (a story that's completely different and infinitely more political). While I find that idea ridiculous (show me a story that HASN'T been done before in some way) I get the idea of that too.

But I'm not talking about any of those things here.

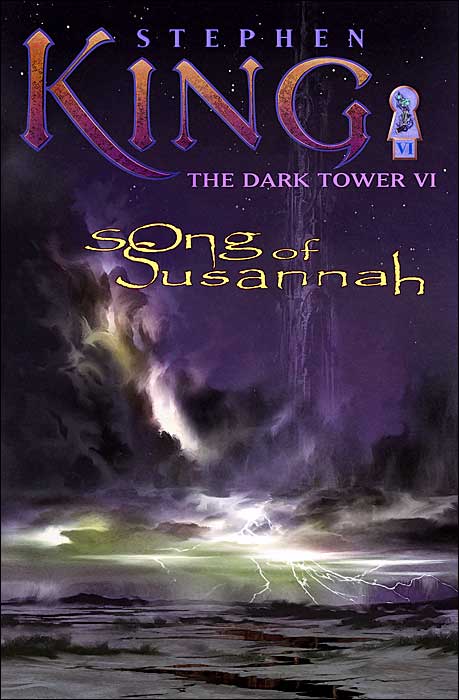

Hollywood has a way of ruining the good parts of the things we enjoy. There was no need for a second Tron movie (even though I kinda loved it). At other times, Hollywood has a way of bringing out the best of a story, making the movie version an instant classic. Two examples of this, both originally written by Stephen King: "Stand By Me" (adapted from his short story called "The Body") and "The Shawshank Redemption" (based on another short story called "Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption").

Gary Ross' vision of "The Hunger Games" falls into the former category and felt a little ruined to me, though there were some fantastic aspects to the movie.

The movie is set up almost as if we, the viewers, are actually watching parts of the Hunger Games. Bits of interviews with the Gamemaker and others involved play out like a show being watched in real time. I think if this had been a more pervasive theme throughout the movie, it would've strengthened some of the weak parts that I'll talk about later.

The movie itself doesn't drown in CGI. In fact, so much of it looks real that I had trouble distinguishing the real from the fake most of the time, and this was great. That lack of falseness that CGI emits made the movie feel very much set in the present moment and lent a credibility to the action that was hard to ignore. Where other dystopian/sci-fi movies have a tendency to embrace the shimmery-ness of special effects, "The Hunger Games" seemed to shrug them off for a more realistic approach. This was the right way of thinking, though it may be harder to avoid in the next film (since I know what happens in the second book).

Katniss, the main character, is played almost to perfection by Jennifer Lawrence (see: "Winter's Bone"). She is strong, but not wholly confident in her abilities. The book is set almost completely inside the mind of Katniss, which makes for some interesting adaptations to the screen. Viewers aren't going to want to listen to every one of her thoughts, but it's her thought processes that sweeten the good moments and make the awful moments that much more gut-wrenching.

Throughout the course of the book, Katniss and her fellow tribute Peeta realize that they'll get more outside help from viewers if they play up the idea of a romance between each other. The moral quandary here is that Katniss doesn't feel the same way about Peeta that Peeta feels about her; she's not a liar or a person who uses others as a means to an end, but ultimately she relents and plays up the romance too. Gary Ross glosses over the moments that could have really gotten into this more in-depth, but instead shied away from highlighting them.

This was not only distracting, but it made some of the later scenes (when Katniss is taking care of a wounded Peeta in a cave) fall so emotionally flat. If I had gone into the theater having not read the books, I would've been scratching my head by the end. The romance felt rushed and without much in the way of being anything Katniss truly struggled with. And this is one of the bigger themes of the later books, which makes it incredibly important in getting set up early on.

There is also the issue of Haymitch (played by Woody Harrelson). A notorious drunk and ex-winner of the Hunger Games so long ago, Haymitch stumbles around for most of the book with a hateful attitude and a flask at the ready. This image of him plays out for a bit in the movie, but then quickly turns into Haymitch being some kind of super-likeable guy by the end (which there are *brief* moments of in the book).

Now I realize there's only so much you can do with a two hour movie as compared to a 400 page book, so I'm trying not to be overly-critical. The movie looked fantastic, set wise. The costumes and the design were all great as well. The acting was solid on everyone's parts, but it was (ironically) the writing of the script that seemed to be the most lacking. And this was even with the original author, Suzanne Collins, on hand to help out. I don't know if perhaps having her on set to adjust the script for adaptation was a good thing or a bad thing, but the movie felt like it tried to cram in a lot of really important details (necessary for viewing the next two movies) into a very short amount of time.

Overall, I think the movie is a success. It looks good, it's acted well, and damn near every character looks exactly the way I pictured them while reading the books. The world of Panem is slightly different than I pictured, but I like it, and with Collins at the helm helping, I'm sure it looks the way she wanted it to and that's good enough for me. Now that the main characters are somewhat fleshed out, I'm hoping that the second and third movies delve more into the interpersonal relationships with the characters, as that's the only way a story will ever truly gel together. Character is of the utmost importance. Hollywood can give you all the actors you need, but if there's no onscreen vibe or chemistry between them, all you've got are people acting out dialogue. And that can get very, very boring.

(7,899)

Sunday, March 25, 2012

(Review) Jeremy Robert Johnson - "Extinction Journals"

I've been trying to find some of the strangest books I can. In part because I'd like to see what sits on the fringe of a normal readership and in part because I want to see if the writing lives up to the hype of the surreal ideas presented in the synopses of these books. The success rate has been pretty middling. While the ideas are there, the writing isn't, or the converse of the writing being solid, but the idea being very lacking in many ways. Regardless, I still try to give these books a chance since I tend to write in the same kind of vein. I recently received "Extinction Journals" by Jeremy Robert Johnson in the mail as my next experiment in this reading list hypothesis of mine.

The book begins at the near end of World War III. Nuclear fallout covers the country and a single man, Dean, walks the countryside wearing a suit made of cockroaches. The first scene of the book finds us in Dean's perspective as he's choking a dying President of the United States at the base of the Washington Monument in a humanitarian effort of keeping the POTUS from feeling the roach-suit eating away at him. The President, however, is also wearing a suit; one made entirely of Twinkies.

I'll let that sink in for a minute.

Then things turn only slightly more sane. Dean wanders the countryside, wondering if the suit of his own making will allow him to eat since they attacked the President so violently, so hungrily. If the suit dies, does Dean die too? Will a suit of dead roaches still protect him from the radiation of the surrounding atmosphere? He doesn't know, but comes across some water with which to slake their thirst just in case. While doing so, a rainbow-colored, scale-covered cyclops riding a flaming chariot comes down from the sky.

Seriously.

This cyclops is apparently the man-made apparition of the quantum energy made up of the cellular moments when people come to an understanding that they're about to die. The collective final moments of the earth's population have essentially summoned this creature to the planet. After some horribly cliched conversation on topics like "wisdom sharing" through "mutually shared frequencies," Dean and the creature learn a bit about where they're both from and why. When the creature finds out that Dean must be the last living person on Earth, he leaves. This whole section read like bad high school science fiction writing and I was glad when it ended. Though the creature leaves with a final thought that may be the best written line of the book:

Dean continues on, walking during the day but allowing the roaches to carry him over distances while he sleeps at night. Weirdly enough, this image makes sense to me. Eventually Dean comes across other dead bodies, all wearing suits of their own: styrofoam man, concrete block man, a woman wearing "two leather aprons and steel-toed workboots on each of her appendages." Finally, Dean comes across a black man named Wendell wearing a skin suit made of a white man who had better luck than him. Wendell soon expires after Dean gives him CPR. The roach suit consumes Wendell.

Oddly enough, the most interesting parts of the book are the times when Dean has no one to talk to. There is an opportunity that Johnson misses by barely touching on the possibility of Dean's mental acuity post-bombings. If this kind of mentality were more explored, the book wouldn't feel nearly as rushed or feel like it had been written by a teenager with a ton of really interesting images, but not a lot of ways to make those images connect in any real meaningful way. The moment Dean realizes that he can mentally control parts of his roach suit to move in their own specific ways shows a moment of high interest with a lot of possibilities. Instead, this moment moves on into another meeting with a completely nude woman named Mave who wears a suit made entirely of ants.

As it turns out, Mave had been an entymologist before the bombings with her co-worker/lover Terry. Both Terry and Mave were visited by the cyclops alien in burning chariot as well, but Terry disappeared shortly after. Mave, who now believes that the alien has endowed them with special powers of some sort (the ants on her, the roaches on Dean), also believes that Terry will find himself endowed with the species of army ants known to war against the species that Mave currently wears (or is actually the Queen Mother of now). She is afraid that the army ants will overtake Terry's weak will, kill him, then hunt her down and devour her (as is their way of living).

As if the first part of this book hadn't been a complete stretch, now we're getting into some really ridiculous plot-rendering. Granted the book is only 84 pages long, but this is at page 67 where I feel like there's an actual point to the story. And Mave seems to be the most well-written character of the whole piece thus far, which isn't a glowing review on the rest of the characters we very briefly run into along the way.

Mave and Dean fall asleep. While they sleep, Dean's roach suit has moved him far away from Mave, who is now being slowly devoured by Terry's ants (who have obviously found the pair). Dean stops his suit from moving him, returns to the scene, but falls into a trap carved out by Terry's ants. The pregnant roaches covering Dean hatch their eggs and the baby roaches scatter up and over Terry, devouring him and put a halt to Mave's pain (since Terry was controlling the ants eating her).

This is essentially the book. I should've known better when I read that Chuck Palahniuk said of the author and his previous book: "A dazzling writer. Seriously amazing short stories - and I love short stories. Like the best of Tobias Wolff. While I read them, they made time stand still. That's great." After reading this one, I want whatever Palahniuk is smoking because this was, on a story and development level, about the bare minimum you could get away with.

This was one of the worst books I've ever read. I can't imagine that his short stories are much better considering it only took me an hour to read this. Great title, great cover art, but I'd probably use all the pages inside it as toilet paper before I ever recommended this book to anyone else.

(7,732)

The book begins at the near end of World War III. Nuclear fallout covers the country and a single man, Dean, walks the countryside wearing a suit made of cockroaches. The first scene of the book finds us in Dean's perspective as he's choking a dying President of the United States at the base of the Washington Monument in a humanitarian effort of keeping the POTUS from feeling the roach-suit eating away at him. The President, however, is also wearing a suit; one made entirely of Twinkies.

I'll let that sink in for a minute.

Then things turn only slightly more sane. Dean wanders the countryside, wondering if the suit of his own making will allow him to eat since they attacked the President so violently, so hungrily. If the suit dies, does Dean die too? Will a suit of dead roaches still protect him from the radiation of the surrounding atmosphere? He doesn't know, but comes across some water with which to slake their thirst just in case. While doing so, a rainbow-colored, scale-covered cyclops riding a flaming chariot comes down from the sky.

Seriously.

This cyclops is apparently the man-made apparition of the quantum energy made up of the cellular moments when people come to an understanding that they're about to die. The collective final moments of the earth's population have essentially summoned this creature to the planet. After some horribly cliched conversation on topics like "wisdom sharing" through "mutually shared frequencies," Dean and the creature learn a bit about where they're both from and why. When the creature finds out that Dean must be the last living person on Earth, he leaves. This whole section read like bad high school science fiction writing and I was glad when it ended. Though the creature leaves with a final thought that may be the best written line of the book:

"And by the way, Dean, I thought you might find this amusing. For a man so singularly obsessed with death, you are hugely pregnant."

Dean continues on, walking during the day but allowing the roaches to carry him over distances while he sleeps at night. Weirdly enough, this image makes sense to me. Eventually Dean comes across other dead bodies, all wearing suits of their own: styrofoam man, concrete block man, a woman wearing "two leather aprons and steel-toed workboots on each of her appendages." Finally, Dean comes across a black man named Wendell wearing a skin suit made of a white man who had better luck than him. Wendell soon expires after Dean gives him CPR. The roach suit consumes Wendell.

Oddly enough, the most interesting parts of the book are the times when Dean has no one to talk to. There is an opportunity that Johnson misses by barely touching on the possibility of Dean's mental acuity post-bombings. If this kind of mentality were more explored, the book wouldn't feel nearly as rushed or feel like it had been written by a teenager with a ton of really interesting images, but not a lot of ways to make those images connect in any real meaningful way. The moment Dean realizes that he can mentally control parts of his roach suit to move in their own specific ways shows a moment of high interest with a lot of possibilities. Instead, this moment moves on into another meeting with a completely nude woman named Mave who wears a suit made entirely of ants.

As it turns out, Mave had been an entymologist before the bombings with her co-worker/lover Terry. Both Terry and Mave were visited by the cyclops alien in burning chariot as well, but Terry disappeared shortly after. Mave, who now believes that the alien has endowed them with special powers of some sort (the ants on her, the roaches on Dean), also believes that Terry will find himself endowed with the species of army ants known to war against the species that Mave currently wears (or is actually the Queen Mother of now). She is afraid that the army ants will overtake Terry's weak will, kill him, then hunt her down and devour her (as is their way of living).

As if the first part of this book hadn't been a complete stretch, now we're getting into some really ridiculous plot-rendering. Granted the book is only 84 pages long, but this is at page 67 where I feel like there's an actual point to the story. And Mave seems to be the most well-written character of the whole piece thus far, which isn't a glowing review on the rest of the characters we very briefly run into along the way.

Mave and Dean fall asleep. While they sleep, Dean's roach suit has moved him far away from Mave, who is now being slowly devoured by Terry's ants (who have obviously found the pair). Dean stops his suit from moving him, returns to the scene, but falls into a trap carved out by Terry's ants. The pregnant roaches covering Dean hatch their eggs and the baby roaches scatter up and over Terry, devouring him and put a halt to Mave's pain (since Terry was controlling the ants eating her).

This is essentially the book. I should've known better when I read that Chuck Palahniuk said of the author and his previous book: "A dazzling writer. Seriously amazing short stories - and I love short stories. Like the best of Tobias Wolff. While I read them, they made time stand still. That's great." After reading this one, I want whatever Palahniuk is smoking because this was, on a story and development level, about the bare minimum you could get away with.

This was one of the worst books I've ever read. I can't imagine that his short stories are much better considering it only took me an hour to read this. Great title, great cover art, but I'd probably use all the pages inside it as toilet paper before I ever recommended this book to anyone else.

(7,732)

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

(Review) Ben Marcus - "The Flame Alphabet"

*SPOILERS INSIDE*

Ben Marcus is a strange dude who writes strange stuff. The first book of his I read was "The Age of Wire & String," which anthropomorphized inanimate objects (a redundant statement, I know) into strange and surreal moments. I won't even pretend to have understood everything I read in that book, but on a surface level, I enjoyed the hell out of its playfulness and its willingness to breach boundaries of normative fiction, a trait I'm finding more and more necessary and required in the authors that I prefer to read these days. I'm not an anti-traditionalist, I've just come to enjoy books as puzzles to be mulled over and solved rather than simply read through from cover to cover. (See my review of Mark S. Danielewski's "House of Leaves" here (pt. 1) and here (pt. 2) for a book-as-puzzle.)

What we get in this latest work by Ben Marcus, "The Flame Alphabet," is something equally as surreal, but infinitely more readable. There is a more structured plot, more clearly defined and delineated characters, an obvious conflict (both highly emotional and highly physical), and a beautiful use of language in many places, which kept the story fresh for me.

I have read other reviews of this book that pan the use of time (moments jump around from now to then to when and back again in the first section without much of a marker to indicate them happening sometimes), but I found the jumps to be completely appropriate and realistic in the storytelling form. We begin the novel with the narrator, Samuel, and his wife Claire fleeing their neighborhood. Both are ill, but specifics are kept to a minimum. As they drive, Claire keeps an eye out for their daughter...not because they're trying to find her, to have her join them in their exodus, but to make sure that the last memory of their child is not one of her being black-bagged and taken away by the government patrols roaming the streets.

Then we backtrack to a more immediate past where Claire and Samuel are getting ill, but not understanding why until they send Claire off to camp for a week. While she's away, the two parents return to a semblance of good health. When she returns, so does the illness. Samuel soon realizes that their daughter is the problem, but doesn't seem to understand why. Esther's character is written as a strange parallel to the contagion; she actively argues and fights with her parents at every turn, utilizing a logic they can't quite seem to fight against. She is headstrong and willful in ways that beat down the parental psyche, ultimately breaking down both Samuel and Claire.

"She spoke to us and others, into the phone, out the window, into a bag. It didn't matter. Nice things, mean things, dumb things, just a teenager's chatter, like a tour guide to nothing, stalking us from room to room."

Another point of note is that they are a Jewish family, getting their sermons not from a normal synagogue, but from a small, hidden hut in the forests made specifically for them. The sermons are fed through wires and cables from an unknown source through a Listener, a strange organic kind of translation machine that sits on top of a hole in the ground that reaches forever deep. Esther is never allowed to join with her parents, however. Like most other Jewish families, the children have their own huts they supposedly go to in order to receive the Rabbi's message. These messages are for the listeners alone and they are NEVER to speak about them to each other, even if they listened to them together. The greater public begins calling them Forest Jews and wonders exactly how much more information they're getting about the widespread illness among the adults.

Murphy, a man Samuel notices one afternoon, appears to be a neighbor that makes Samuel uneasy. He doesn't seem to be Jewish, but hints at things one could only know through the specific broadcasts in the forest huts. Couple that with the fact that these missives aren't supposed to be talked about, and you've got Samuel not only uncomfortable, but incredibly suspicious of this new person. Over the course of the first section, as things get progressively worse, a strange connectivity blossoms between the two men. Philosophical musings on the nature of trying to find a cure highlight the nature of both men. Samuel seems to be the odd optimist where Murphy seems to be more nihilistic in his approach, having already tried everything Samuel is doing now.

"Failures have their place in our work," [Murphy] admitted, after hearing me out. "I've had my flirtations with failure. There is a small allure there. I commend you for seeking out failure so aggressively. But this idea people have of failing on purpose, failing better? Look at who says that. Just look at them."

By the end of the first section, we come to find out that Murphy isn't who he says he is, but possibly three or four other people of some notable mention. Samuel and Claire's hut is broken into, deconstructed by a "thief" while Samuel stands in the doorway and listens to him speak. We also watch as Claire and Samuel prepare to leave Esther alone in their house, spiriting away to places that may provide better coverage from the children causing whatever this spoken contagion is. The adults are dying, withering away, crisping, and familial bonds break, splinter, and shatter so that people can live.

If part one can be seen as the more emotional attack about the contagion, allowing the reader to watch as Samuel decides how he feels about both his wife and his daughter, then part two is most certainly the more rational, scientific (see: clinical) attack. It begins with the entire city overrun by "medical officials" corralling the adults out of town. They comb the fields and forests, making sure to leave no one behind. During the first few hectic moments, Claire escapes from the car and heads toward a nearby field where she is quickly scooped up and placed in a van. Samuel is made to leave the city without her, leaving with barely a shrug as to his wife's vanishing.

He travels across the state to Forsythe, which he finds out is a high school turned medical facility. Experiments are being done on language and he becomes a worker bee, trying to find a "script" that will allow for communication without contagion. After several days of doing his own experiments (for there are no directives or instructions given to him), he realizes that his purpose is to work towards a way of creating some kind of communication that doesn't cripple those around him. He muddles with cuneiform, different shades of text with different writing implements, code...until finally a result is shown to himself and the others.

It is also fitting that, in this clinical environment, the idea of personal touch becomes depersonalized, broken down into simple stimulus response passages. The "workers" at Forsythe simply tap each other on the shoulder when they want to have sex with someone, but it is a loveless, joyless sex, a coupling of withered bodies containing broken minds and stilled tongues.

"We may as well have withdrawn my emission by syringe. The glow of orgasm was so vague, I experienced it as a theoretical warmth in the adjacent wall, as something atmospheric nearby that I could appreciate, but that I myself barely noticed. When I reached climax with Marta, I felt the material vacate my body, which counted for something, but the accompanying gush had departed, relocating off-site. It might as well have been happening to someone else. Perhaps it was."

Eventually, Samuel comes face to face with the person in charge, who extorts the well-being of Claire (newly found and inside Forsythe) in exchange for Samuel's help getting to the hidden layers of communications being pumped through the orange cables at a Jew Hole in the basement. He does as he's asked, is given personal time with Claire, but then plans an escape through the Jew Hole. After realizing he has no way of getting closer to her, he leaves Claire to fend for herself in the compound.

Part three begins three years later. Samuel and Esther live in the old Jew Hole hut out in the forest. No one lives in the houses any more and the adults all wait outside the Child Quarantine areas, hoping either to exact revenge for the hurtful speech of years past or to find their children whom they've been separated from for so long.

It is this final act that, unfortunately, feels the least interesting. Hot emotion in part one, clinical studies and hypotheses in part two, but part three seems to be filled, ironically, with hope. After so much dark thinking and so many tongues hardened in the mouth from speechless years, this evocation of Samuel's hope for the future of his family is both ironic and sad, but seems to ring less true than the more surreal aspects of the book that came before it. But, the final part is mercifully short and does not, in my mind, ruin the book in any way.

I think the ideas proposed in the last few pages are appropriate in a way that isn't saccharine. It's too easy to write an ending that is over-the-top chintz and happily ever after. Marcus ends the book perfectly as a foil to the beginning of the book. Samuel's journey from start to finish is poignant and apt. At times he made me wish I could strangle him while other times had me praising his thought process. Overall, I would highly recommend this book, if only for the multitude of lines like this (from the end of the second section):

"What is it called when a dark, hard magnet has been run over one's moral compass so many times that the needles of the compass quivers so badly that it cannot be read?"

(7,552)

Wednesday, March 14, 2012

Friday, March 9, 2012

Artist Profile Submissions

I've got two already and I'd love to have more up here as I know TONS of artists from across the country. Sculptors, Painters, Photographers, etc...

If you happen to be one of these people and would like me to help promote your work and your websites, please follow these instructions.

Email me at authorbuch@gmail.com with "ARTIST PROFILE" in the subject heading. Feel free to attach as many pictures of your work (along with titles) and a short bio (how long you've been creating, past shows or places where your work has been shown, shows that you have coming up in the future, etc.). The more information, the better. The aim is to promote your work as fully as possible to a wider audience.

IN THE EMAIL:

Attach pictures of your work and please answer these questions...

1.) Why are you an artist?

2.) What is your inspiration?

3.) Would you consider yourself a designer or artist or both?

4.) What is your philosophy of Art?

5.) What is the role of the artist in our society?

6.) Where do you see yourself as an artist in 5 years? What are your ultimate goals as an artist?

7.) What does art mean to you?

Again, the more in-depth the answer, the better. A response that's only a line or two doesn't give anyone any insight into who you are or what/why you do what you do. Feel free to get wordy.

Feel free to pass this along to anyone you may know that wants a little free exposure too.

Also, I know of no way to protect pictures, so if you've got watermarked versions you'd prefer using, that's TOTALLY perfect in case you're concerned with that.

Get at me. I know there's a ton of talent out there that's not getting enough exposure and I'd like to change that for as many people as possible.

(6,998)

Thursday, March 1, 2012

Artist Profile: Makenzie Darling (San Francisco)

Makenzie Darling

Makenzie attended Suffolk University where she majored in Women's Studies and Fine Art. Her main mediums were acrylics, oils, and colored pencils. Her concentration centered around feminism and religion; specifically the constant power struggle for women between the forces of good and evil. Much of it revolved around Adam and Eve and Christianity as a whole. Serpents appear in a lot of her earlier works that represent evil and temptation.

She gave up art for six years until she moved to San Francisco, where she took up collage work. Her later work is influenced by the surrealists and are primarily dreamscapes or fantasy lands; places where people can escape. Some still have to do with the balance between good an evil, as found in the piece titled "Dreams Progressions."

"Dreams Progressions"

"Anarchy"

Why are you an artist?

Art is a true escape. It is the only time where I'm able to truly be honest with myself, listening to my subconscious. Art has been a form of therapy, for me to work through my demons and bring my innermost fears and desires to light. When I'm doing my art, I become lost in the process and all else that is trivial melts away.

"Bridge to Dali"

"Freedom"

What is your inspiration?

I went to a catholic school when I was younger and became mesmerized by religion, especially the cultivation of women's oppression throughout the Bible. A lot of my earlier work has to do with the balance and fight between good and evil. This fight was mirrored in my personal life as I was trying to overcome a tumultuous relationship with my mother who was often portrayed as the serpent in my work.

"Tree"

"Adam & Eve Kissing"

Would you consider yourself a designer, an artist, or both?

I am an artist in every sense of the word. I don't create for others, but only paint and collage to express my innermost thoughts and feelings.

"Concrete Garden of Eden"

What is the role of the artist in our society?

Art can serve many different roles. The purpose of some arts is to make people happy and bring them joy, through a simple, yet beautiful, still life. Other art is made for people to question themselves and the society that they live in. This art often angers people, but it's an anger that brings about different perspectives, which excites me the most. Lastly, art can play a connection. It can take something that you have thought or felt and bring it to life on canvas, making you step back and say "I feel the same way and yet...I would have never thought to portray it in that way."

"Lucky Strike"

Where do you see yourself as an artist in 5 years? What are your ultimate goals as an artist?

Quite honestly, I don't have a five-year plan and never really have in anything I do. If I had bet five years ago that I would be where I am today, I would be straight-up broke. I think, for me, being an artist means surrendering the master plan and trying to work on your art as much as possible. Personally, I don't do my art for other people so much as I do it for myself. I may never have a show at an art gallery, but my living room walls inspire me daily.

"Chanel Number 5"

"Starlight"

What does art mean to you?

Art is freedom. In my personal life, I bring a lot of energy and strength to those around me. I am constantly thinking of others and neglect my own needs a lot of the time. Painting and collage are the only times when I can turn off my brain, be by myself, and look inward. It's raw, beautiful, creative, spiritual, and vulnerable. It's the true me that not many people get to see.

"Buddha"

(6,600)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)